When we think of the most important events of the past 100 year, certain years are particularly crucial in determining the course of history. Among the most important are those that marked the end of a period of conflict and the beginning of a new era of peace, namely: 1918/19 (End of WWI, Peace of Versailles), 1945 (End of WWII, beginning of the United Nations), and 1989 (end of the Cold War and the new era of globalization). However, for this blog, I would like to point to one lesser known year that marked not only the end of a period of conflict or start of peace, but also the beginning of a new period of global interactions, which, for better or worse, still shape the world we live in today.

Why 1979?

In the year 1979, several major events occurred around the world. I will list them by geographic region (East Asia, the Americas, and the Greater Middle East, in no particular orders of importance), and then discuss the impact of each of these events.

In East Asia:

The events in East Asia revolved largely around what China had done during that year. Two important event occurred:

- China’s economic reform and opening up: In December 1978, during the 3rd Plenary Session of the 11th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China, a national meeting of China’s policy-makers, a new national political and economic policy was implemented. First, the meeting confirmed the role of Deng Xiaoping as the undisputed leader (or “Paramount leader”) of China. Deng had been well known as a reformer who wanted to implement changes to China’s bureaucracy and the way the economy was run. Secondly, in part due to the first, a new national economic policy was set whereby a new model of economic organization was first introduced in the countryside (the Household Responsibility System), and leading to a dramatic increase in agricultural productivity and output. These reforms marked the first stages in the transformation of China from an economic backwater into one of the fastest growing economic entity of the past 35 years.

- China and Vietnam fought a brief border war: The Sino-Vietnamese war of 1979 (or the Third Indochina War) was nominally fought over the Vietnamese invasion of Cambodia, whose Khmer Rouge government was supported by China, and at least launched in part by China to test Soviet resolve in defending its Vietnamese ally. However, the real significance of the war was not in the conduct of the war itself, but rather what the war represents. First, the conflict was the last conventional war in East and Southeast Asia. After a series of on-and-off conflict among East Asian nations from 1931 (when Japanese forces first invaded China) to 1979, the nations of East Asia is finally at peace with one another. During this period, the clashes of a variety of ideologies such as militarism, colonialism and anti-colonialism, national and ethnic nationalism, and finally communism all served to fuel a state of continuous conflict in the region. The end of the conflict also marked the beginning of a period of rapid economic growth for not only China, but also for other nations of Southeast Asia. The trajectory of East Asian history was forever altered after 1979.

The Americas:

The role of the United States during this time period cannot be exaggerated. It was the world’s foremost economic power; and by most measures, the world’ leading military power as well. The economic difficulties experienced by the United States during the latter half of the 1970s can be explained as an economy in transition from an export-oriented industrial economy to one based on services and high-tech information, along with a significant rise in imports for manufacturing goods. Nevertheless, the United States faced two difficulties as its economic output continues to grow, all with respect to energy:

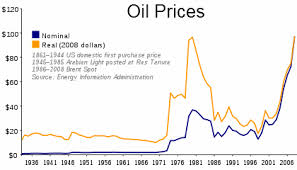

- The Second Oil Shock: In 1973, the United States experienced what is later termed the First Oil Shock, whereby, due to a confluence of factors such as a tightening of the oil market (where supply is barely keeping up with demand), instability in the oil producing regions, and finally an outright embargo on the part of the OPEC (Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries) against the United States for its role in supporting Israel, led to a massive increase in the price of oil. However, this Second Shock of 1979 was due to quite different causes. The Iranian Revolution (to be discussed below) led to a sudden increase in the price of oil as several million barrels of oil were removed from the market. This event helped to trigger a recession in the United States, along with significant political fallouts for President Carter and the Democratic Party, and marked the rise of conservative, neoliberal thinkers in economic circles (The Chicago School of Economics, mot vocally represented by Milton Freidman). Moreover, the Oil Shock leads to increasing financial instability in the US and Europe, and helped to make an already fragile economic situation even worse by introducing an element of inflation along with economic stagnation into the economy.

- The nuclear meltdown of Three Mile Island: The nuclear accident at Three Mile Island (a partial meltdown) was another significant event in the energy landscape of the United States in 1979. The accident, while not particularly significant in terms of destruction or radioactive materials released, did lead to a change in perceptions in the public eyes on the issues of nuclear power. This event helped to energize the environmental movement on the issue of nuclear power, and eventually this led to a freeze on all new nuclear power plant construction in the United States. Nuclear energy, which had seemed so promising to many Americans as a reliable source of energy, had now been relegated to the fringe. Another consequence of this event is the increasing dependence of the United States on petroleum as an energy source. Increasingly, the United States began to intervene on a larger scale in oil-exporting regions to ensure that a reliable source of energy supply does not become a problem for the United States.

Greater Middle East:

- Soviets invaded Afghanistan. The Soviet Union, through the invasion of Afghanistan in support of the Afghan communist government, in effect launched a series of chain reactions that had the most profound consequences today. First and foremost, the Soviets hastened its own collapse by expending an extraordinary amount of resources (something that it cannot afford due to its fragile economic situation), in both manpower and money. In addition, the image of the Soviet Union as offering an alternative to the “imperialism” of the United States was destroyed, and its influence in the world stage declined drastically. More importantly for the trajectory of world history, the conflict generated a huge response across the Islamic World, in both fighters and money, in support of the “holy war” conducted by the resistance fighters (known as the mujahedeen) to the Soviet Union. Over time, the conflict takes on an increasingly religious nature, where it is seen by many Muslims as a conflict to end the oppression of the Afghan people. Thus, Political Islam in its modern form was born. Another event also took place during the latter half of the conflict which have strong ramifications today. Among the thousands of young foreign Jihadists was a young man by the name of Osama Bin Laden. Indeed, it is in Afghanistan that Al-Qaeda first started. It is important to note the name Al-Qaeda translates as “The Base”, the base by which Islamists in Afghanistan organized themselves and fought against Soviet aggression.

- Islamic extremists took control of the Grand Mosque of Mecca: In late 1979, religious militants took over the Grand Mosque of Mecca and openly challenged the Saudi family’s religious authority. (The Sauds have claimed in their title that they the “Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques.) Later, Saudi security forces moved in and forcibly cleared out the insurgents, resulting in hundreds of causalities. The event, played out on televisions in the Arab World, shocked many who watched it. At the time, many in the Islamic world, from Philippines to Turkey to Pakistan, blamed the United States and Israel for this attack, which in turn led to massive demonstrations, including the burning of US embassy in Pakistan and Libya. The perpetrators were dealt with harshly, and all 68 rebels were captured and beheaded. However, what is truly significant about this event was that the role of religious authority in Saudi Arabia did not diminish after this attack. Instead, the religious conservatives were given more power. In order to appease the religious scholars and social conservatives, the Saudi government turned toward religion to uphold their own legitimacy. Religious schools became more prevalent; the social roles of women were cut back, and in some cases were removed from public altogether. After 1979, Saudi Arabia increasingly became a religious theocracy, with profound influence on the rise of Political Islam.

- Iran’s Islamic Revolution: The final event in the Middle East that is crucial to our understanding of the year 1979 was the conservative Islamic revolution in Iran. By the end of 1978, the government of the Shah of Iran was in its last throbs. The question facing many Iranians was not whether or not the Shah should go, but rather, what sort of government should replace it. The solutions were far ranging, from the Tudeh Party (Communist Party of Iran) to religious ultra-conservatives. While the average Iranian was debating and fighting among those alternatives, the Shah suddenly left the country and left a large power vacuum in a country where the heavy hand of the state had been ever present. Into this power vacuum, an exiled religious teacher – Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini – made a landing in Iran. The masses suddenly found a leader that they can unite themselves around, and within weeks, a religious theocracy, as though something coming out of the Middle Ages, was born. The Ayatollah possessed hatreds towards many groups around the world – communists (both inside and outside the country), Israel and the Zionists, and above all, the “Great Satan” in the form of the United States. This hatred only increased over time as he gained more political power. The impact of the Revolution can be seen immediately, from the Iranian Hostage Crisis with the United States to the inauguration of the decade long war with Iraq, all stemming from this watershed event of the Middle East.

Now that we have come to the end of our list of major events of 1979, I would like to make note of a few more things:

First, even though in this article I have treated world events as separate in their geographic scope, in reality, all of these events are intimately connected and one often feeds off the other. For instance, American dependence on foreign oil increased just at the same time as Iran’s Islamic Revolution, which removed several million barrels/day from the world market; the fuel crisis of 1979 was certainly worsened by the conflicts in the Middle East. No event in the world took place in isolation, and each one influenced and shaped the outcome of the other.

Secondly, due the scope of this article, I am unable to discuss many of the important events in detail, but they are often important in their own right. 1979 was a year of many changes, yet it has frequently been ignored by many who are not as familiar with world history. I hope that through this article, I can at least spark some interests among my blog readers in the world around us, and view current events through a historical lens.

Finally, the history of the world since 1979, the fall of the Berlin Wall, the War on Terror since the early 2000s, the economic rise of China and increasingly East Asia as a whole, the challenges and benefits of globalization, all directly or indirectly traced their root to the tumultuous year of 1979. In many ways, the events of 1979 is still influencing the world around us, and we are still living in its shadows.

d be crazy.” Although his words may seem extreme, we need to understand what motivated the Iranian leadership to develop nuclear power, even in the face of mounting international oppositions. The Iranians’ own argument is that they need to secure their own energy needs in the form of nuclear power. This argument is hardly plausible: Iran is sitting on the world’s second largest reserves (after Russia) of natural gas. Iran’s South Pars gas field alone is estimated to contain 14×10^12 m3 of gas, around 5.6% of the entire world’s prove gas reserves. Moreover, the country contains the 4th largest reserves of oil in the world. Iran’s energy needs can largely be satisfied by its oil and natural gas, as can be seen in the chart below.

d be crazy.” Although his words may seem extreme, we need to understand what motivated the Iranian leadership to develop nuclear power, even in the face of mounting international oppositions. The Iranians’ own argument is that they need to secure their own energy needs in the form of nuclear power. This argument is hardly plausible: Iran is sitting on the world’s second largest reserves (after Russia) of natural gas. Iran’s South Pars gas field alone is estimated to contain 14×10^12 m3 of gas, around 5.6% of the entire world’s prove gas reserves. Moreover, the country contains the 4th largest reserves of oil in the world. Iran’s energy needs can largely be satisfied by its oil and natural gas, as can be seen in the chart below.

least) by most governments around the world. Strategically, Russia can be considered an ally, but that nation is struggling in the face of western sanctions for its involvement in the Crimea and a falling oil price. (For a discussion of how falling oil prices are influencing foreign policies in Russia and Iran,

least) by most governments around the world. Strategically, Russia can be considered an ally, but that nation is struggling in the face of western sanctions for its involvement in the Crimea and a falling oil price. (For a discussion of how falling oil prices are influencing foreign policies in Russia and Iran,

Chinese housing market be at a turning point, and is perhaps already on a road to decline? Recently, I have read that some in China have begun to starting selling their houses, and that those who sells it the most are those with government connections. Perhaps they have some insider information on the Chinese government’s attempts to curb this housing bubble, or that they know something the rest of people in China do not? In terms of policy, I believe the best way to do this is through tightening the credit market, and raising interests rates. Its been well known that the government have been trying to do curb the proliferation of non-performing loans and easy money that is circulating in the country, and if the central bank indeed decided to raise the interest rates, the effects could be extremely profound, not only for the housing market, but for the entire economy. The construction boom occurring in China is fueled by the essentially free-loans that real estate developers have been getting through state-owned banks, many of these using their political connections. And now the housing supply have far outstripped the demand for housing, yet the price remains artificially high, with most of the new buying coming from speculators. In this situation, a crash is inevitable. Many have warned that crash is impending for many years now, yet the market took the warning in stride, perhaps factoring in the risk. Yet investors still believed that the boom is sustainable. In such a situation, even the slightest sell-offs can induce a panic.

Chinese housing market be at a turning point, and is perhaps already on a road to decline? Recently, I have read that some in China have begun to starting selling their houses, and that those who sells it the most are those with government connections. Perhaps they have some insider information on the Chinese government’s attempts to curb this housing bubble, or that they know something the rest of people in China do not? In terms of policy, I believe the best way to do this is through tightening the credit market, and raising interests rates. Its been well known that the government have been trying to do curb the proliferation of non-performing loans and easy money that is circulating in the country, and if the central bank indeed decided to raise the interest rates, the effects could be extremely profound, not only for the housing market, but for the entire economy. The construction boom occurring in China is fueled by the essentially free-loans that real estate developers have been getting through state-owned banks, many of these using their political connections. And now the housing supply have far outstripped the demand for housing, yet the price remains artificially high, with most of the new buying coming from speculators. In this situation, a crash is inevitable. Many have warned that crash is impending for many years now, yet the market took the warning in stride, perhaps factoring in the risk. Yet investors still believed that the boom is sustainable. In such a situation, even the slightest sell-offs can induce a panic.