It is generally accepted by economists that discrimination is an influential factor in affecting the functioning of a modern day economy. Theories regarding discrimination – its impacts on the global economy and possible solutions to the problem – have been debated and argued by influential economists over the decades. A key question that we ask ourselves is: will the market regulate itself and be able to eliminate discrimination, or does the government have to intervene? If so, what is the best approach to government intervention? This question can be seen as a part of the larger debate between the neoclassical economists and the Keynesian economists over the role of government in our economies and social lives.

This problem of whether or not to regulate the issue of discrimination has been debated by politicians and economists over the years, especially since discrimination is not only an economic issue, but also a social one. Historically, governments have taken a generally laissez-faire approach to economics in society, and regulations are few, especially in the US. This changed dramatically starting in the late 19th century, with the emergence of populist movements such as women’s suffrage, and accelerated dramatically during the two World Wars and the Depression era, when governments began to take a more active economic role in society and mandated fairness in hiring in order to receive federal funding. Finally, the Civil Rights movement of 1950s and 60s pushed the issue to the forefront and the government enacted broad legislations regarding labor employment practices. Two of the most notable legislations of the period are the Equal Pay Act of 1963 and Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The Equal Pay Act have stated that firms should take into consideration a person’s gender in the determination of wages using the theory that that the same amount of work deserve the same amount of pay. Title VII of the Civil Rights Act made it illegal to discriminate based on a person’s “race, color, religion, sex or national origin”, and implemented a comprehensive list of anti-discriminatory methods.

However, in more recent years, the problem of discrimination takes on a new turn with the rise of “Deregulation” and the stepping away of government from some of its historic stances on promoting more equality in the market-place, and igniting the debates anew.

The current consensus is, in a way, a reaction against the free-market advocates, which have become especially popular in the US since the 1980s. In fact, it has been argued by economists that discrimination has increased from the ‘80s onward, in large part due to the popularity of this line of argument. We can examine this opposite side of the argument by looking at the positions taken by two of the greatest economists of the latter twentieth century: Milton Friedman and Robert Lucas. Friedman had argued that the free market will resolve the problem of discrimination itself because discrimination is inefficient in the long-run (“Capitalism and Freedom”, 1962). In one of his most often quoted passages, he stated “It is a striking historical fact that the development of capitalism has been accompanied by a major reduction in the extent to which particular religious, racial, or social groups have operated under special handicaps in respect of their economic activities; have, as the saying goes, been discriminated against.” Friedman believed that the employer’s self-interest will cause them to overlook the other categorical attributes of an individual in favor of whoever can work the cheapest for the most amount of productivity.

The current consensus is, in a way, a reaction against the free-market advocates, which have become especially popular in the US since the 1980s. In fact, it has been argued by economists that discrimination has increased from the ‘80s onward, in large part due to the popularity of this line of argument. We can examine this opposite side of the argument by looking at the positions taken by two of the greatest economists of the latter twentieth century: Milton Friedman and Robert Lucas. Friedman had argued that the free market will resolve the problem of discrimination itself because discrimination is inefficient in the long-run (“Capitalism and Freedom”, 1962). In one of his most often quoted passages, he stated “It is a striking historical fact that the development of capitalism has been accompanied by a major reduction in the extent to which particular religious, racial, or social groups have operated under special handicaps in respect of their economic activities; have, as the saying goes, been discriminated against.” Friedman believed that the employer’s self-interest will cause them to overlook the other categorical attributes of an individual in favor of whoever can work the cheapest for the most amount of productivity.

On an interesting note, Friedman was himself the subject of discriminations during his times at the University of Wisconsin at Milwaukee, and one of the chief reasons he chose the University of Chicago for its PhD program was due to its open and more tolerant environment. In a sense, Friedman affirmed the idea that discrimination is detrimental to the employer (in this case the university) by “voting with his feet” to a location that was more tolerant.

Writing along a similar line, Robert Lucas stated that any irregularity in the “Market” introduces a distortion that will resolve itself over time. And in his view, government attempts in ending discrimination will simply introduce new inefficiencies in the marketplace that has to be resolved. What both of these economists suggested is that firms are very rational and they pursue the maximum amounts of profits possible. In order to do this, it only makes them to only care about costs and benefits, and since race/ethnicities/gender, etc. does not have a specific benefit or cost associated with them, firms will not discriminate. For those firms that do discriminate, in the long run they will become inefficient and the competition will eliminate them from the marketplace. The free market is the best left alone, according to Friedman and Lucas, since the mechanism of incentives in a rational society will help to eliminate discrimination and get rid of these inefficiencies.

Meanwhile, the mainstream have taken the view that in order for discrimination to be solved, the markets must be regulated through governmental legislations and acts. They are essentially arguing for a top-down, command-and-control method in regulation approaches to enforce those regulatory methods. Many noted that more regulation has been the historical trends, as more legislations have come on board over the years to prohibit certain behaviors from employers. They outlined two main approaches by governments to combat discrimination. The first is what is generally referred to as “Nondiscrimination” where employers are essentially blind to race, ethnicity, or sex, and to determine that those factors should not play any role in the selection of workers (This is the principle behind the Equal Pay Act). The other approach is termed “Affirmative Action”, where employers MUST take race, ethnicity, and gender into account to ensure fair representation, especially for historically disadvantaged groups. These two approaches have proven to be somewhat contradictory, i.e. how to ask ask employers to be blind to the differences between workers while at the same time be cognizant of the fact that certain groups should be considered more highly, holding other factors constant? This contradiction made it difficult to implement some of these methods in ending discrimination, and it is somewhat flawed as a result.

In addition, Title VII also distinguished between disparate treatment and disparate impact; where disparate treatment is defined as being proof that the workers are intentionally being discriminated against, while disparate impact are defined as result from actions, however unintentional, that results in some groups being disproportionately impacted. All of these are important considerations for firms that are trying to avoid discrimination.

In cases where it can be difficult to implement equal for equal work, they introduced the idea of comparable worth to help measure employee value. Often, many noted, it is impractical to “achieve equal pay for equal work”. Therefore, some have supported the goal of equal pay for jobs of “comparable worth”, and what determines the comparable worth is market forces. Comparable-worth policies have generally relied on job-rating schemes by employers to determine or justify pay differentials. However, this job-rating scheme is highly subjective and subject to great controversies.

As a case example, many pointed to the example of the Federal Contract Compliance Program, where governments monitor hiring and promotion practices of federal contractors. This program utilized affirmative action to ensure that groups that have been historically disadvantaged received preferences. In terms of absolute numbers, the federal contract compliance program increased opportunities for minority groups tremendously. The concerns with these programs is that when underrepresented groups are given preferences in hiring, this might result in less qualified workers being hired. And since the programs only covered the federal contractors, it is possible that while the program attracted talented minorities, there might be no overall gains in employment due to other sectors of the economies being neglected. As evidence of the effectiveness of the government programs, some have pointed out that government policies have distributed new employment opportunities among federal contractors towards blacks and Hispanics. The ratio of black to white incomes has risen since the 1960s, but we cannot effective draw causation relationships between this and the governmental legislations.

Finally, the mainstream believed that it is important to continuously monitor the economy to catch discriminators. One way to do this is to conduct an audit where blind experiments are conducted, telling auditors to look at firms and measure the effects of discrimination. However, these studies are very difficult to conduct since the auditors cannot know the purpose of the experiment (since that will introduce an element of bias), while at the same time, they are very difficult to conduct due to cost constraints. In another famous experiment, which has since been replicated worldwide, experimenters send out resumes to a number of different firms. It was found that white-sounding names needed 10 resumes to receive one call back, while black sounding names required 15 resumes to receive one call back, a 50% difference in employer response rate. However, even this experiment can be subject to bias, as the names may in themselves be a signal on the quality of the workers, and not necessarily having anything to do with race itself. For instance, it is possible to have a name of “Jared” being associated with a bad worker, but not necessarily to that person’s race.

I believe that while the the mainstream’s position is elegantly argued for, and we agree with the general premise that the markets need to be regulated. However, I believe that regulations may not work in all cases. The solutions many economists presented are excellent, but may not be adequate since it doesn’t allow a degree of freedom to the individual to decide in specific cases of discrimination. Governments can do a number of other things that can combat the effects of discrimination, besides direct, top-down regulation. I believe that the government should embrace a comprehensive, top-down approach in fighting discrimination, while at the same time, it might work with other players in the market so that anti-discriminatory laws can be used effectively and efficiently.

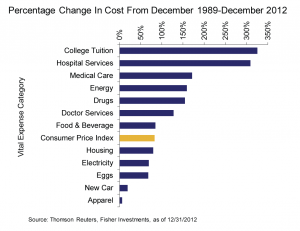

Firstly, I believe that free markets are efficient in the sense that it generally can allocate resources as needed to the market actors. Markets generally have a very remarkable ability to become efficient with the right incentives. However, in the case of discrimination, it may become inefficient due to the lack of those incentives. In many cases, discrimination can be good for businesses since they are able to charge different wages to different individuals, and they are able to get the same amount of work out of some workers while costing a fraction of the wage expense. This has historically been the case with what we call the “gender wage gap”, where men and women are paid different wages for essentially the same amount and quality of work. In addition, we often see firms hire workers whom they or their employee knows well (a network effect). This can be discriminatory because the results (disparate impacts) can be discriminatory in nature. The only way to solve these issues is by having firms being regulated directly by the government to change the historic legacy.

Secondly, I believe that governments should take a leading role, but not the only role in helping to end discrimination. A government’s approach should be based on both “carrot” and “sticks”. Governments can directly punish the worst discriminatory offenders, while at the same time, they offer incentives to encourage diversity in the workplace. Governments should consult the private sector to see why they may not want to hire women/minorities, and work with them to help design incentives to help end discrimination.

Thirdly, governments can also utilize other methods that are not direct regulations, for instance through education in non-discrimination. This in fact has been promoted in the schools’ educational curriculum in the past few decades and have been credited with helping new generations of workers and employers understand the value of diversity in the workplace. Educational changes can cause the deepest changes in the way workers interact with others and in a firm’s hiring practices. In many cases, the markets simply are not aware of the potential benefits a diverse workforce can bring along, and it takes some educational efforts, in part facilitated by the government, to change the firm’s hiring practices.

Lastly, I believe that the free movement of people has been extremely beneficial for firms and discriminatory practices would stop this free movement of people. Government should do all it can to make sure that worker mobility is not impacted, as historically, workforces that move around tend to reward firms that are the fairest and most efficient at utilizing labor. For instance, during mass construction projects that are undertaken by the government or large corporations in the past, people of different ethnicities often come and work together, albeit sometimes on different parts of the same project (i.e. the transcontinental railroad). This has been very beneficial for the employers as they are able to attract the best talents due to the mobile workforce.

To conclude, I believe that our solution is a compromise between the neoclassical, free-market advocates on the one hand, and the regulation-heavy advocates on the other. Businesses exist in an environment where discrimination exists and governments need to ensure that workers do not encounter discrimination through regulations, workplace incentives and education programs. At the same time, governments need to consult with private companies to see what works best to end discrimination. A collaborative environment between governments and businesses, we believe, is often the best one in ending discrimination. Behind all of these proposals in ending discrimination is our firm belief that markets, when given the right incentives, will come to the rational conclusion: Discrimination results in an inefficient utilization of resources, firms will lose out on some of the best talents, and in the long run, only firms that do not discriminate can survive in our global, interconnected world.

heavily shorted stocks (as measured by short interests) in the US are in the restaurant sector. Restaurants in general are low-margin, with high fixed costs, with tremendous competition, and susceptible to variances in consumer sentiments. All of these makes them good companies to avoid investing in at any given time. But in 2015, there are macroeconomic factors at play here as well. Even though the US economy have outperformed its peers in the developed economies, consumer disposable incomes have not risen appreciably over the past year or so. Americans simply aren’t spending as much on restaurants as before, and the growing competition for healthy food options left many traditional restaurant chains and fast-food restaurants little options but to change what they are offering to clients. These changes will take a long time to implement, and will be extremely costly, even if they are successful at all. (McDonald’s recent advertising campaign is a good example of a restaurant trying to reshape their brand image).

heavily shorted stocks (as measured by short interests) in the US are in the restaurant sector. Restaurants in general are low-margin, with high fixed costs, with tremendous competition, and susceptible to variances in consumer sentiments. All of these makes them good companies to avoid investing in at any given time. But in 2015, there are macroeconomic factors at play here as well. Even though the US economy have outperformed its peers in the developed economies, consumer disposable incomes have not risen appreciably over the past year or so. Americans simply aren’t spending as much on restaurants as before, and the growing competition for healthy food options left many traditional restaurant chains and fast-food restaurants little options but to change what they are offering to clients. These changes will take a long time to implement, and will be extremely costly, even if they are successful at all. (McDonald’s recent advertising campaign is a good example of a restaurant trying to reshape their brand image).